|

| Richard Strauss |

The king of the waltz, Johann Strauβ, is the same last name, and I, personally, often mistake them, but they are different people and have different composition styles.

The only thing I like among many of his works is the violin sonata in E♭.op.18 I will introduce now.

A more virile, heroic or masterful declaration of intent than the earliest of Richard Strauss's odyssey of tone poems, his Don Juan, Op.20, would be unimaginable.

But in 1888 when Strauss catapulted his Don into a musical world ill prepared for either seduction or duels, he unwittingly sounded the death knell for its older siblings!

Neither of the early works heard on this recording is widely performed today, yet each marked a significant watershed in Strauss's creative development.

Strauss's Opus 18 violin sonata in E flat (the key of Beethoven's Eroica and Strauss's own Heldenleben) was completed in 1887, when the composer was 23. With two symphonies, the symphonic fantasy Aus Italien, the cello sonata, concertos for horn and violin, a string quartet and the Burleske for piano and orchestra already behind him, Strauss was no compositional novice.

While the violin sonata inhabited that same domain as those by Brahms and Franck (written just months earlier), it foreshadowed Strauss's mature style in microcosm.

Consider its lavish chromaticism, the short, pithy, brilliantly deployed motivic fragments, the sensational, unyielding virtuosity, the prominence of Strauss's much-vaunted six-four chord, and, not least, the inevitable choice of key!

Strauss's last chamber work (but for the lovely string sextet that would open his opera Capriccio in 1942) begins with an Allegro of remarkable fertility, presenting four quintessentially Straussian ideas in a structure that moves unexpectedly from 4/4 into metre and back. Even the gripping first subject, writes Michael Kennedy in the New Grove, "tends to break the bonds of its format," anticipating the unforgettable opening measures of Don Juan in the process. The central movement, improvisation, seems to have been composed last; there are fleeting glimpses of Schubert's Erlkonig in the piano part, as the violin muses enigmatically, perhaps echoing Mendelssohn's Songs Without Words. The movement proved so popular (and so playable!) that Strauss authorized its publication separately, though several commentators, among them Abram Loft (in his authoritative study Violin and Piano- the Duo Repertory), have unjustly rejected it as "uneven cabaret music." But every source agrees that the Finale, which poens with a brief slow introduction, is at once gloriously assured and miraculously predictive of future achievements.

For a long time, two friends who had been together as chamber partners gathered together for a long time. Click the description below the photo to connect to YouTube.

Their ensembles are in ten fingers. That's so cool! Click the description below the photo to connect to YouTube.

A more virile, heroic or masterful declaration of intent than the earliest of Richard Strauss's odyssey of tone poems, his Don Juan, Op.20, would be unimaginable.

But in 1888 when Strauss catapulted his Don into a musical world ill prepared for either seduction or duels, he unwittingly sounded the death knell for its older siblings!

Neither of the early works heard on this recording is widely performed today, yet each marked a significant watershed in Strauss's creative development.

Strauss's Opus 18 violin sonata in E flat (the key of Beethoven's Eroica and Strauss's own Heldenleben) was completed in 1887, when the composer was 23. With two symphonies, the symphonic fantasy Aus Italien, the cello sonata, concertos for horn and violin, a string quartet and the Burleske for piano and orchestra already behind him, Strauss was no compositional novice.

While the violin sonata inhabited that same domain as those by Brahms and Franck (written just months earlier), it foreshadowed Strauss's mature style in microcosm.

Consider its lavish chromaticism, the short, pithy, brilliantly deployed motivic fragments, the sensational, unyielding virtuosity, the prominence of Strauss's much-vaunted six-four chord, and, not least, the inevitable choice of key!

Strauss's last chamber work (but for the lovely string sextet that would open his opera Capriccio in 1942) begins with an Allegro of remarkable fertility, presenting four quintessentially Straussian ideas in a structure that moves unexpectedly from 4/4 into metre and back. Even the gripping first subject, writes Michael Kennedy in the New Grove, "tends to break the bonds of its format," anticipating the unforgettable opening measures of Don Juan in the process. The central movement, improvisation, seems to have been composed last; there are fleeting glimpses of Schubert's Erlkonig in the piano part, as the violin muses enigmatically, perhaps echoing Mendelssohn's Songs Without Words. The movement proved so popular (and so playable!) that Strauss authorized its publication separately, though several commentators, among them Abram Loft (in his authoritative study Violin and Piano- the Duo Repertory), have unjustly rejected it as "uneven cabaret music." But every source agrees that the Finale, which poens with a brief slow introduction, is at once gloriously assured and miraculously predictive of future achievements.

|

| 2mv. improvisation: andante cantabile |

For a long time, two friends who had been together as chamber partners gathered together for a long time. Click the description below the photo to connect to YouTube.

|

| Kyung wha Chung & Krystian Zimerman |

Their ensembles are in ten fingers. That's so cool! Click the description below the photo to connect to YouTube.

|

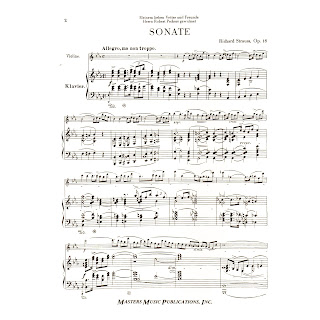

| 1 movement sheet |

0 댓글